I became a geologist almost by chance. I enrolled the physics department of the University of La Sapienza, Rome, Italy, because as a boy I had a passion for astronomy. I had my head in the clouds often, or better, I was lost in space. My high school maths and physics teacher in Italy, Gabriele Rago, made us dream about parallel universes, fourth dimension and time travel. He was a genius and by studying with him I was able to shape a scientific mindframe, I learned how to use my own brain and even how to think different. I wouldn’t have made it without him, I wouldn’t have been capable of graduating on a scientific subject. After my graduation, I felt I had to to thank him, although I had switched to Geology right after my enrollment: I had set my feet “on the ground” after I realized I made the wrong choice. I had to “fall back” on a different subject, though still a scientific one. I had never heard about it, I was advised by other students who made the same “mistake”.

I became a geologist almost by chance. I enrolled the physics department of the University of La Sapienza, Rome, Italy, because as a boy I had a passion for astronomy. I had my head in the clouds often, or better, I was lost in space. My high school maths and physics teacher in Italy, Gabriele Rago, made us dream about parallel universes, fourth dimension and time travel. He was a genius and by studying with him I was able to shape a scientific mindframe, I learned how to use my own brain and even how to think different. I wouldn’t have made it without him, I wouldn’t have been capable of graduating on a scientific subject. After my graduation, I felt I had to to thank him, although I had switched to Geology right after my enrollment: I had set my feet “on the ground” after I realized I made the wrong choice. I had to “fall back” on a different subject, though still a scientific one. I had never heard about it, I was advised by other students who made the same “mistake”.

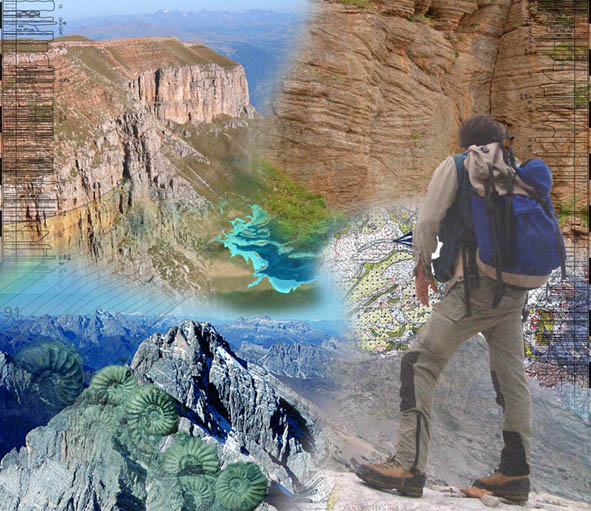

At the beginning it was not easy anyway. I didn’t feel the subject was really mine. I went on just drifting, making no fuss about it. Deep inside, I still felt guilty about having surrendered too early and abandoned my dream of becoming an astrophysicist. But after a couple of non enthusiastic years, I started to attend classes that changed the way I saw things. Maurizio Parotto of the University of Rome is not just a professor, he is a real gifted teacher. His unlimited passion for geology exuded contagiously during his classes. It reached deep inside myself. When his classes were over I felt sorry, I craved for the next one so I could discover how it went on. It was like watching one of David Attenborough’s documentaries. I was caught! Those classes made me feel that everyday I made a new discovery. I felt the urge of telling someone else how beautiful it was. I would have loved becoming a teacher of that kind. I still treasure the notes from his classes. Even during field trip training, he passed his passion down to me and allowed me to become one of those geologists who, armed with compass, lens and hammer, walk the countryside looking for clues of the geological history of an area. Those unforgettable classes made me wish one day could teach geology, too. I dreamed about introducing geology to people on their first approach to the subject. I’d want to pass down my passion to them, opening their eyes to a different view on our planet, a living one, one that changes in geological time, something only a geologist may be aware of.

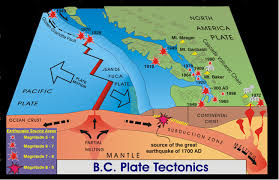

But the following year I suffered a “spiritual crisis”. None of the classes I attended was even comparable to the amazing documentary/classes of the year before. What really depressed me was the idea that the new classes dealt with what was seen as the actual job of a geologist, the so-called “applied geology” used in building constructions or hydrogeology. They didn’t seduce me at all. I was tormented by a doubt: did I make it all wrong? I didn’t know I would have hated working as a geologist if it had to be in construction industry. Had I known before, I certainly wouldn’t have never picked up geology. The geology I learned to love the year before was a science – that was why I was fascinated. What should I do? What kept the flame still burning inside me was the late Renato Funiciello’s structural geology class, a great friend of Parotto’s. Studying crustal deformation, folds and faults felt like there was a continuity with what excited me so much just one year earlier.

I found out that structural geologists work for oil companies and their knowledge is fundamental in identifying the geological structures that trap hydrocarbons underground. I found myself deeply fascinated by tectonics and by the chance to work one day for a hydrocarbon research and exploration company. What really interested me was not oil or gas in particular, but the high quality of geological studies involved in hydrocarbon research. If it wasn’t for oil and gas exploration, most of the scientific progress in geology would not even exist. The availability of subsurface seismic and well data from oil companies is like gold for scientific research, which could never afford such money investments. That knowledge takes the form of hydrogeological or seismic (or geologic in general) risk maps, clearly very useful to the community. The exchange between research and industry in this field is among the most profitable and fundamental.

I graduated in 1991 with a thesis on structural geology with Prof. Funiciello with a dream of finding a job in an oil and gas company.

Some teachers made me dream. I still bring that dream inside me. It supported me through the long years of unemployment and petty jobs that followed. Without that dream I would have quit. Who knows what I would have done in my life? I held on instead, I never stopped dreaming, I kept on reading those notes that made me fall in love with Geology. When I accepted a different kind of job, I saw Geology flying away from me, farther and farther any day. I could not accept it. I kept my memory alive, refreshing the concepts, rewriting my own geology notes as I would have liked to teach them. I sent CVs all around the world. But finding anything besides constructions was hard and I had absolutely no interest in the subject whatsoever. After my first real job as a geologist, I had the chance of working for years in the same university where my old professors were still teaching. I was back in my dream and I couldn’t believe it. I had the chance to teach some geology on the field, engaging the students to use their own reasoning when observing the landscape and the outcrops. Italian universities are what they are. Professors are never judged for their teaching abilities or devotion to classroom work. Only research counts, and being in the right place at the right time, with the right people. There was no room for me. I still dream of becoming a teacher, who knows, maybe one day, abroad.

Some teachers made me dream. I still bring that dream inside me. It supported me through the long years of unemployment and petty jobs that followed. Without that dream I would have quit. Who knows what I would have done in my life? I held on instead, I never stopped dreaming, I kept on reading those notes that made me fall in love with Geology. When I accepted a different kind of job, I saw Geology flying away from me, farther and farther any day. I could not accept it. I kept my memory alive, refreshing the concepts, rewriting my own geology notes as I would have liked to teach them. I sent CVs all around the world. But finding anything besides constructions was hard and I had absolutely no interest in the subject whatsoever. After my first real job as a geologist, I had the chance of working for years in the same university where my old professors were still teaching. I was back in my dream and I couldn’t believe it. I had the chance to teach some geology on the field, engaging the students to use their own reasoning when observing the landscape and the outcrops. Italian universities are what they are. Professors are never judged for their teaching abilities or devotion to classroom work. Only research counts, and being in the right place at the right time, with the right people. There was no room for me. I still dream of becoming a teacher, who knows, maybe one day, abroad.

As a geologist, I have worked in a small oil and gas exploration company for a few years. Unfortunately, it didn’t last long: a certain vulgar or “taliban” environmentalism, the so-called nimby-effect, plus the stupidity of our administrators are causing foreign investors to lose confidence in putting their money in our country. As a result, I have been forced to stop being a geologist… well done, Italy!